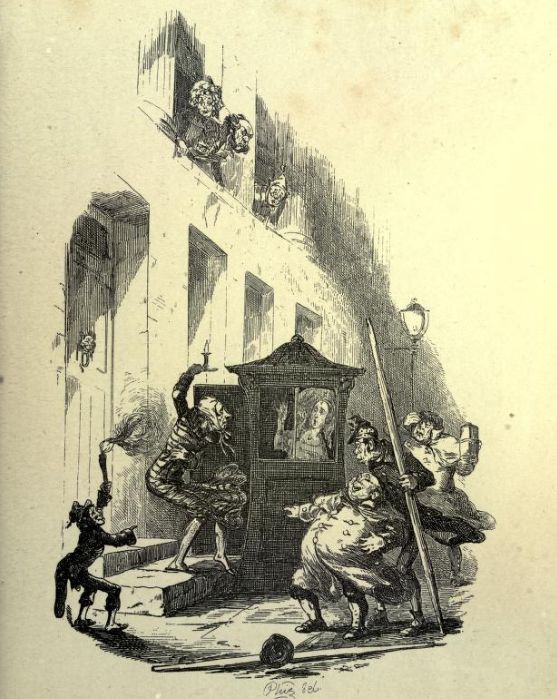

We are in London, 21 November 1817, two years after Waterloo, and Charles and Mary Lamb have just moved from the relative quiet of the inns of court to ‘a place all alive with noise and bustle’, and she is loving it, as she tells Dorothy Wordsworth. The linkboys, who carried burning torches to guide the theatre-goers home, would soon be put out of business by gas lighting. Some gas lamps still illuminate parts of Covent Garden. A gas lamp, a linkboy and a candle in this illustration from the Pickwick Papers, and still people are in the dark!

At last we mustered up resolution enough to leave the good old place that so long had sheltered us—and here we are, living at a Brazier’s shop, No. 20, in Russell Street, Covent Garden, a place all alive with noise and bustle, Drury Lane Theatre in sight from our front and Covent Garden from our back windows. The hubbub of the carriages returning from the play does not annoy me in the least—strange that it does not, for it is quite tremendous.

I quite enjoy looking out of the window and listening to the calling up of the carriages and the squabbles of the coachmen and linkboys. It is the oddest scene to look down upon, I am sure you would be amused with it. It is well I am in a chearful place.

From The Letters of Charles and Mary Lamb, 1796-1820 , edited by E. V. Lucas.

Now, of course, it’s black cabs and Uber! Enjoy the Gas lights of an evening visit to Covent Garden.